For the citizens of Pateros, cityhood is a chance to improve the municipality’s stature vis à vis the 16 other cities in NCR, save its ailing industries, and raise the standard of living of its people – tasks that have proven difficult to accomplish.

Pateros’ seemingly long-shot claim to its “historical” territory just got a new lease on life.

In April of this year, the Supreme Court (SC) clarified that Pateros is not a party to its previous decision favoring Taguig over Makati concerning the fate of ten disputed barangays. Moreover, the SC ordered the Pasig City Regional Trial Court (RTC) to reinstate a case Pateros filed in 2012. This case involves Pateros’ pursuit of the lands covered by Parcel 4 of Survey Plan Psu-2031.

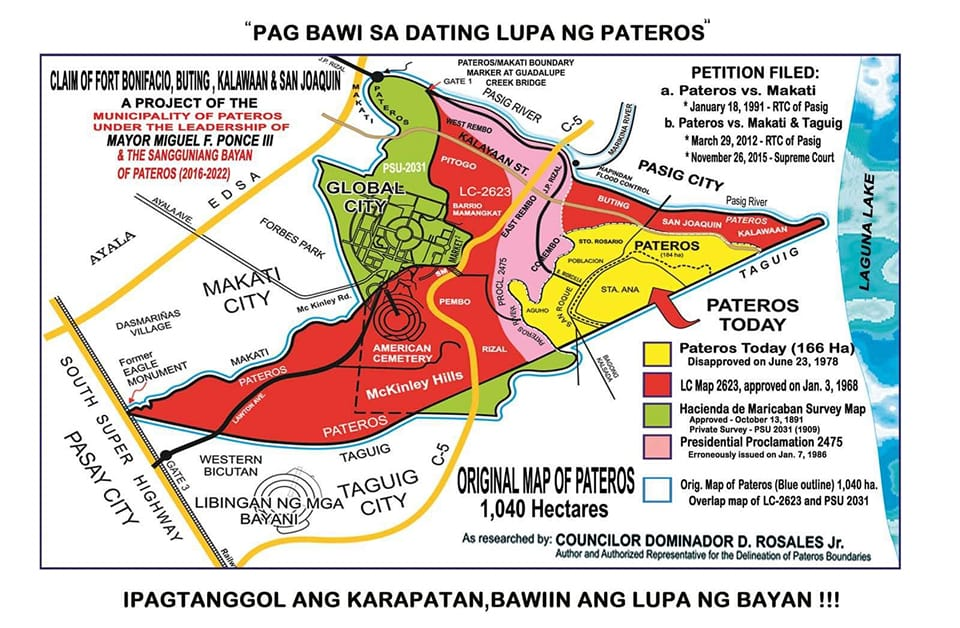

Parcel 4 has an area of more than 760 hectares, covering Bonifacio Global City, Barangay Pitogo, and seven Enlisted Men’s Barrios (EMBOs): Barangays Cembo, South Cembo, West Rembo, East Rembo, Comembo and Pembo.

In an interview with One PH, Pateros Mayor Miguel “Ike” Ponce III expressed confidence that the lone municipality in the National Capital Region (NCR) can prove that BGC and its surrounding barangays truly belong to it. Contrary to how several pundits have framed Pateros as a new entrant to the territorial dispute between Makati and Taguig, Ponce reminded the public that Pateros’ fight to recover its original territory has now spanned over three decades.

Although the components of Pateros’ full territorial claim overlap with those of Makati and Taguig, it can be argued that the political and economic stakes are much higher for the municipality. As the smallest (in terms of land area) and least populous Local Government Unit (LGU) in Metro Manila, Pateros has struggled to grow its economy, help its ailing industries to survive, and find enough space for a talipapa, let alone a thriving business district.

The extent and basis of Pateros’ territorial claim

According to Samahan Ukol sa Ikauunlad (SUSI) ng Pateros, a non-governmental organization committed to delineating Pateros’ boundaries, the municipality originally had 1,040 hectares of land when it was incorporated into a town in 1801 – a far cry from its current territory of 168 hectares.

The SUSI map shows that if Pateros’ 1801 boundaries were to be observed today, the municipality’s northernmost point would reach EDSA while its southwestern tip would extend to the South Super Highway. Pateros would also cover three barangays under Pasig City in its northeast: Buting, San Joaquin, and Kalawaan, which all sit at the southern portion of the Pasig River.

Meanwhile, BGC, the EMBOs, McKinley Hills, the Manila American Cemetery, and other surrounding barangays would be located at Pateros’ center. These areas were previously part of the 766-hectare Hacienda de Maricaban (one of the vast estates that comprised much of NCR before the American occupation) and of Barrio Mamancat (one of Pateros’ five initial barrios).

In 1902, the American colonial government bought Hacienda de Maricaban and turned parts of it into Fort William McKinley and Nichols Air Base. In 1957, Fort McKinley became Fort Andres Bonifacio and served as headquarters for the Philippine Army and Marines. However, Pateros’ saga of territorial loss began when President Carlos Garcia issued Proclamation No. 423 on 12 July 1957 which reserved parcels of public domain within NCR and Rizal for military purposes. Although the proclamation did not mention Pateros, these areas were recognized as officially part of the municipality well into the 1960s.

Three decades later, two presidential proclamations amended Proclamation No. 423 which negated Pateros’ control over the disputed areas. The late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. issued Proclamation No. 2475 on 7 January 1986, stating that Fort Bonifacio was part of Makati. On 31 January 1990, President Corazon Aquino affirmed Makati’s jurisdiction over the EMBOs through Proclamation No. 518. Unlike the first two proclamations, Proclamation No. 518 mentioned Pateros as an involved LGU.

Since the 1990s, Pateros has asserted its ownership of BGC, the EMBOs, and surrounding barangays by engaging in amicable discussions with Makati and Taguig and filing petitions before various forums. However, the Pateros LGU’s efforts are yet to bring back an inch of “historical” territory to the municipality.

A timeline of petitions

While the tit-for-tat between Makati and Taguig has recently gained traction in the media, mentions of Pateros have been scant despite the municipality’s consistent assertions of its territorial claim. Here is a brief timeline of the Pateros LGU’s efforts at reaching out to its fellow claimants and filing petitions before the courts.

1990: Following the issuance of Proclamation No.518, Pateros requested a dialogue with the Municipal Council of Makati.

1991: On 18 January, Pateros filed a petition against Makati before the Pasig City RTC concerning the lands covered by Parcel 4.

1996: Pateros filed a separate case against Makati before the Makati City RTC. However, the RTC dismissed the case on the grounds of lack of jurisdiction.

2003: Pateros appealed its Makati RTC case to the Court of Appeals but was denied once more. In 2009, the Makati RTC case was elevated to the Supreme Court but was also denied for undertaking a wrong mode of appeal.

2009: In a decision penned by Associate Justice Antonio Eduardo B. Nachura, the Supreme Court determined that the dispute must be settled amicably by the respective legislative bodies of Pateros, Makati, and Taguig.

2012: Pateros filed Civil Case No. 73387-TG before the Pasig City RTC Branch 271. The case sought a judicial declaration that the 766-hectare Parcel 4 is within the jurisdiction of Pateros.

2014: The Pasig City RTC junked Pateros’ case for failing to comply with the specified procedures for settling territorial disputes among cities and municipalities.

2015: The Court of Appeals affirmed the Pasig City RTC’s 2014 decision, stating that Pateros was unable to present new and compelling arguments.

2023: The Supreme Court granted Pateros’ petition for review and ordered the Pasig City RTC Branch 271 to reinstate Civil Case No. 73387-TG. The SC also dismissed the previous rulings by the Pasig City RTC and the Court of Appeals junking Pateros’ petitions. Pateros’ case is independent of the Supreme Court’s previous ruling favoring Taguig over Makati concerning the fate of ten disputed barangays.

In a span of three decades, the trajectory of the territorial dispute has often changed. However, Pateros’ motivation for recovering “historical” territory has remained the same: revenue generation, economic growth, and raising the municipality’s profile on the national stage.

Cityhood, balut, and economic vitality

As the lone municipality in NCR, Pateros has often seen itself as a David going up against Goliaths in the quest to recover its “historical” territory. Unlike its neighbors Makati, Taguig, and Pasig, Pateros cannot boast of a deep revenue pool, a large and vibrant business district, or a set of generous welfare benefits for its citizens.

For the citizens of Pateros, cityhood is a chance to improve the municipality’s stature vis à vis the 16 other cities in NCR, save its ailing industries, and raise the standard of living of its people – tasks that have proven difficult to accomplish.

For instance, Pateros has had to work with a smaller National Tax Allotment (NTA) share than its neighboring cities. The NTA is the portion of national taxes dedicated to helping LGUs perform functions devolved from the national government. As a result of the Mandanas-Garcia ruling, the NTA expanded the source of LGU shares from mere revenue collections (which was the case with the Internal Revenue Allotment (IRA). Twenty percent of the NTA goes to the provinces, 34 percent to municipalities, 23 percent to cities, and 20 percent to the barangays.

However, there are almost 1,500 municipalities sharing 34 percent of the NTA total compared to only 149 cities sharing 23 percent. The NTA also divides tax shares based on the geographic and population size of LGUs. As cities generate more revenue on their own, to begin with, small and less wealthy municipalities are left at a disadvantage.

Although Pateros is a first-class municipality, a 2005 land use classification report showed that it is 91.62 percent residential, leaving only 4.40 percent for commercial, industrial, and agricultural use. Census data since 2000 also show that Pateros, aside from being the least populous, is only one of two LGUs in NCR to have experienced a dip in population. Currently, Pateros shares a Lower House representative with Taguig’s first district whose population of over 400,000 dwarfs Pateros’ 65,227. Taguig City Mayor Lani Cayetano used to represent the joint Taguig-Pateros legislative district.

Taking back “historical” territory may well be the missing piece in Pateros’ quest to become a city.

“I believe we should become a city by necessity. Kung mananatili kaming municipality, maiiwan talaga kami,” said Pateros Mayor Ike Ponce in an interview with BusinessWorld last 16 February 2017.

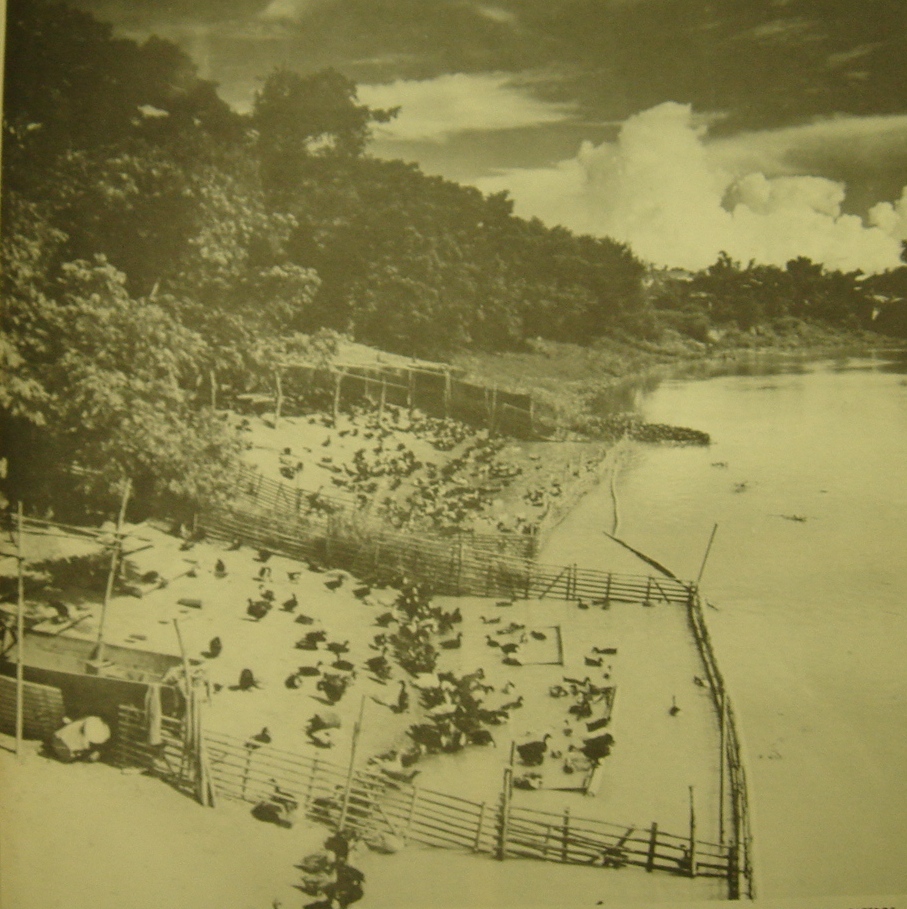

Pateros is known for balut, a popular delicacy made of incubated duck eggs. However, duck raising is now a dead industry in the municipality due to lack of space, pollution, and rapid urbanization. Although Pateros has resorted to outsourcing duck eggs from provinces in Central and Southern Luzon, the balut, penoy, and itlog na maalat industry is struggling to survive.

To diversify and revitalize the municipality’s economy, the Pateros LGU has tried courting Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) companies. However, Pateros’ 168 hectares could not accommodate the infrastructure necessary to see such ventures through, let alone cityhood.

What happens next?

For now, the Pateros LGU is determined to make its case before the Pasig RTC. Mayor Ponce is confident that the municipality is ready not only to recover its “historical” territory, but also to obtain financial proceeds that Makati and Taguig have collected while administering the disputed areas.

The Supreme Court’s recent decisions also mean that Pateros’ territorial claims may figure prominently in the upcoming campaign for the Barangay and SK Elections.

According to Vhon Ventura, an SK aspirant from Barangay Tabacalera, a Pateros victory in the territorial dispute bodes well for cityhood prospects and the municipality’s growth and development relative to its wealthier neighbors in NCR.

“Magkakaroon ng greater opportunity ang bawat barangay sa Pateros lalo na ang SK, dahil hindi na magiging ganoong kababa ang tingin sa Pateros. May potensyal na maging isang ganap na lungsod na ang Pateros,” Ventura asserted in an interview with UP sa Halalan.

What better way for Pateros to reintroduce itself to the consciousness of Filipinos than by reclaiming its “historical” territory?

Enzo Miguel M. De Borja is a BA Political Science graduate from UP Diliman and a Project Assistant for UP sa Halalan 2023. He is also a Program and Research Associate at the De La Salle University – Jesse M. Robredo Institute of Governance.