by Asst. Prof. Nelson Cainghog

Lawmaking is a complex process. It involves many actors performing their respective roles in a long process of deliberation and scrutiny. These deliberations sometimes spill into the wider public expanding the range of opinions that needs to be considered. In the Philippines, this complexity is made complicated through a system of bicameralism. Bicameral comes from the Middle English word bi- meaning two and the Latin word camera or room. Our legislature, the Philippine Congress, is bicameral since it has two chambers, the Philippine Senate as the upper House and the House of Representatives as the lower House.

But why complicate the law-making process by having two chambers when other places do well with just one chamber—a unicameral legislature? The provinces of Canada, the states of Queensland in Australia and Nebraska in the USA all have unicameral legislatures.

For one, a bicameral legislature is, in general, more complex than a unicameral legislature. The same process of deliberation and scrutiny usually happens in both chambers sometimes resulting to different versions of policies. Such differences need further effort at reconciliation through a bicameral conference. The repetition of processes and the need for a bicameral conference would be avoided in a unicameral system.

Second, a bicameral legislature is relatively more expensive. For example, this year 2013, the Senate has a P3.3 billion peso-allocation while the House of Representatives has P6.3 billion. If we will only keep one chamber—usually the House of Representatives—we would be able to save P3 billion annually, equal to roughly four refurbished Hamilton-class cutters of the BRP Gregorio del Pilar kind for the Philippine Navy or roughly 3000 classrooms at P1.1 million per classroom for our schools.

Third, a bicameral legislature is less conducive to change. For instance, under our system we have a Senate composed of twenty-four senators and a House of 287 representatives. Policy proposals that that could hurt vested interests would theoretically be more efficiently blocked in Senate. It is more difficult to influence 145 members of the House compared to just 12 in the Senate. It is also more conducive to gridlocks when chambers could not resolve policy differences thereby delaying much needed reform legislation.

But law-making is not all about time and money, at least ideally. It is also about legitimacy. The United States, for instance, opted to have a bicameral legislature to resolve the debate on states’ representation in the union’s legislature. Large states prefer representation according to state population while smaller states prefer equal representation among states. The Great Compromise was forged giving an upper house (the US Senate) with equal representation among states and a lower house (the US House of Representatives) with representation based on state population. Notwithstanding its complexity and propensity to gridlocks, the bicameral system lends legitimacy to the law-making process by equally representing parochial or district and state-wide interests.

In the Philippines, the function of the upper House is to serve as a check to the parochialism of the lower House. For instance, in 2009, the House of Representatives under Speaker Prospero Nograles approved House Resolution No. 1109 constituting itself as a constituent assembly for the purpose of amending the 1987 Constitution. If there was no Senate at that time, they would have been successful in changing parts of the Constitution to align with their interests. But each chamber’s purpose of checking the other chamber would be effective only to the extent that each have different interests. Check and balances work best when, as James Madison said, “ambition must be made to counteract ambition”.

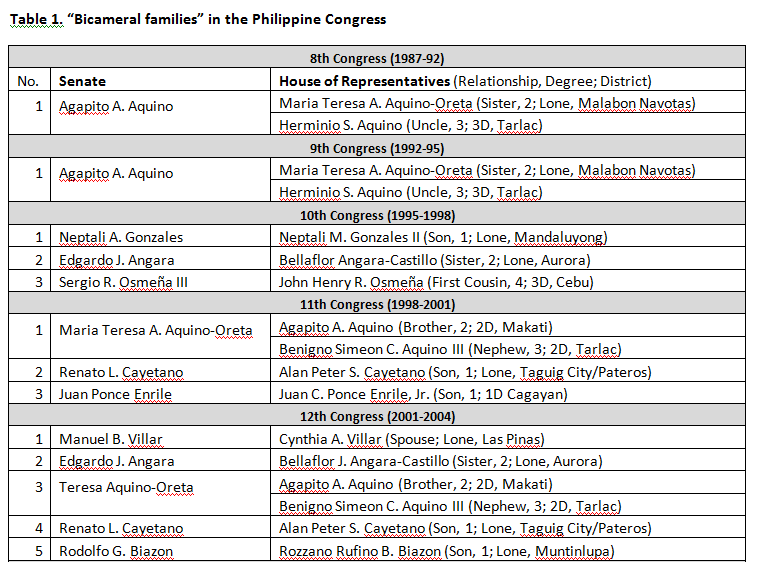

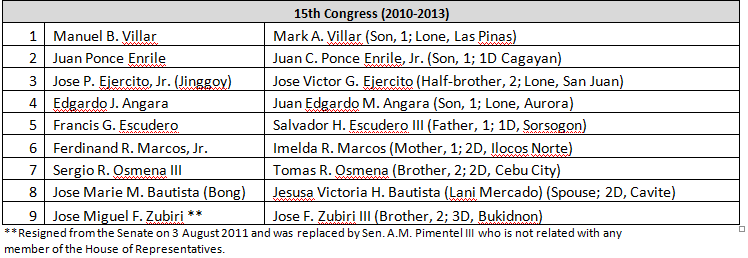

However, a noticeable pattern is emerging in the Philippine Congress where families are not anymore contented of being represented in one chamber. Increasingly, “bicameral families” are emerging where family members within the fourth degree of consanguinity or affinity simultaneously occupy positions in both chambers. While there is no law prohibiting “bicameral families” and its implications to policy-making are yet to be studied, there is an interesting increase of such cases since the 8th Congress, the first Congress after EDSA Uno and a supposed restoration of democracy (see Table 1 below). During the 8th Congress, there were two bicameral families, the Aquinos and the Laurels. This decreased to one after Sen. Laurel lost in the 1992 elections. However, the number increased to five in the next six years (10th and 11th Congresses). Subsequent congresses registered further increases with six and seven in the 12th and 13th Congress, respectively. The last two congresses (14th and 15th Congresses) had nine bicameral families, roughly double compared with the 10th and 11th Congresses. While nine is small in the House of Representatives, it is slight more than a third of the Senate’s membership.

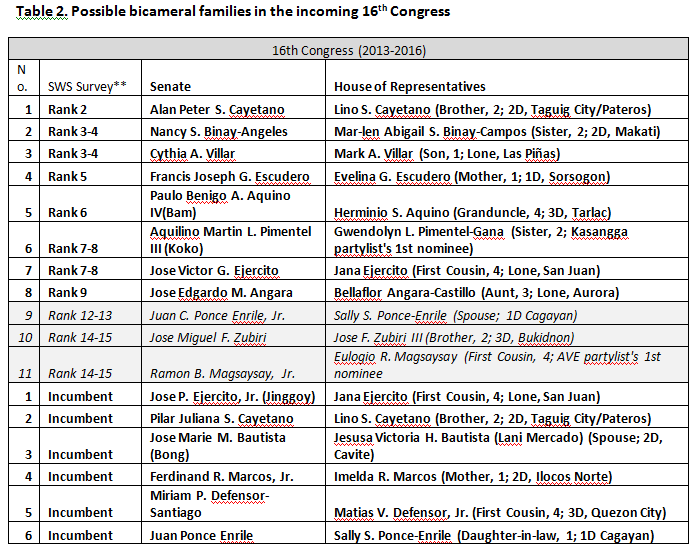

In the incoming 16th Congress (2013-2016), the number of bicameral families is expected to at least remain at nine. At most it will become ten, if Sen. Koko Pimentel’s sister will successfully enter the House of Representatives through the party list system. Just the same, the trend is towards an increased number of bicameral families since the first post-EDSA Uno Congress.

The list of bicameral families features families that would easily qualify into a political dynasty, defined as having a family member succeed a term-limited public official. For instance, Pia Cayetano, Bong Revilla, Koko Pimentel succeeded their fathers in Senate. Sonny Angara is strong poised to do the same. Cythia Villar is also set to succeed her husband. In the House of Representatives, Sally Ponce-Enrile got the mandate to succeed her husband Jackie Ponce Enrile, son of Sen. Juan Ponce Enrile. Evelina Escudero also got the number to win his late husband’s congressional seat. Angara-Castillo also won to succeed her nephew Sonny. Like political dynasties, bicameral families are not prohibited by law. But families with members in both chambers of Congress are doubly influential as they can promote their interests in both chambers. This is not desirable considering that each chamber is supposed to check the other. When political dynasties also become bicameral families, they concentrate power through time and across institutions. Democracy is supposed to be premised on political equality, but the increasing frequency of political dynasties and bicameral families in Philippine politics seem to manifest that some families are “more equal” than others.

Nelson Cainghog is an Assistant Professor of Political Science from the University of the Philippines-Diliman. He recently finished his master’s degree at the Australian National University and was a recipient of the Australian Government’s prestigious 2011 Endeavour Postgraduate Awards.