by Prof. J. Prospero De Vera III

The 2013 senatorial election is shaping up to be the most media-scrutinized campaign in Philippine history. Compared to previous elections, media networks have aggressively organized debates among the thirty three senatorial candidates either on their own or in partnership with academic institutions and civil society organizations. Social media has also weighed in on the credentials, platforms, and promises of the candidates by carrying live streaming debates or producing infographics of candidates’ positions. The University of the Philippines through its Halalan 2013 election project (www.halalan.up.edu.ph) conducts a “fact check” on what candidates say during the television debates.

But do debates really count in shaping the voters choice in the Philippines?

There is no question that debates are important in an electoral contest to know a candidates fitness for public office. But the political context under which the debate is done, its format and structure, and the media pick-up of the event often fails to give voters the needed answers on who should be given the mandate to represent their interests in government.

Even in the most celebrated democracy in the

Rather than convince the uncommitted voter, presidential debates in the US tend to reinforce already existing views on candidates. Both Democrats and Republicans tune in to the debates to strengthen their belief in their respective candidates and mobilize those in their party to support their choice.

If debates in the US have produced mixed results, it has not worked in the Philippines over the past elections. Despite refusing to attend any of the debates, Joseph Estrada won the 1988 elections and Fernando Poe Jr. won (or was cheated in) the 2004 version.

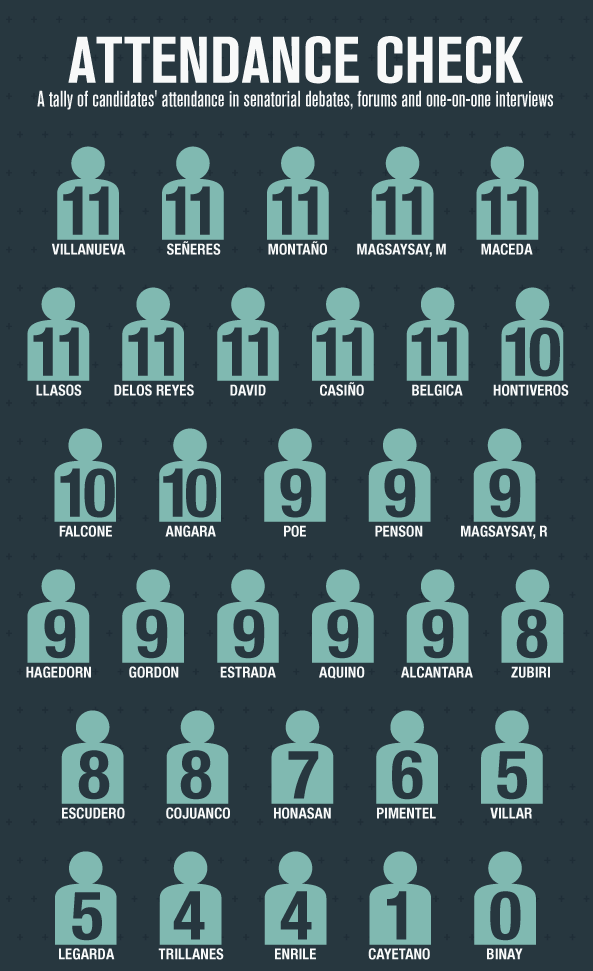

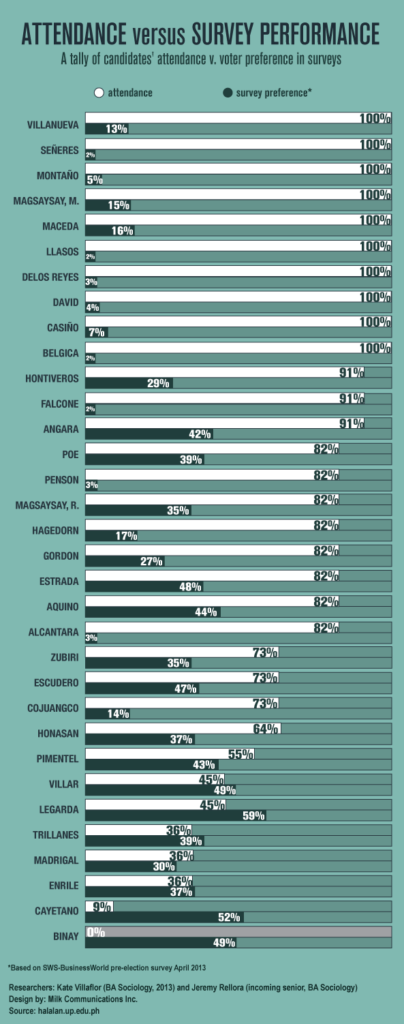

The on-going senatorial campaign seems to validate this same conclusion. The UP Halalan 2013 team monitored the attendance of senatorial candidates in the major television debates and found out that some, such as Nancy Binay, remain strong in the surveys despite refusing to attend any of the debates. Binay and Enrile have been pilloried in social media for their refusal to attend debates, or debate against other candidates with little effect. Some candidates (Cayetano, Trillanes, Legarda and Villar) attended less than half of the debates and continue to get strong voter preference.

And why do the other candidates attend these debates? It seems that the debates attract independent candidates, those lagging behind in the surveys, and those who can’t pay for expensive television ads. They try to maximize free television time to increase voter awareness or try to brand themselves with issues such as “anti-dynasty”, “flat tax”, “securitization”, or some nice sounding buzzwords that, unfortunately, some fail to adequately explain (http://halalan.up.edu.ph/index.php/the-elections/factcheck/153-belgica-on-pork-barrel-funds-and-education-vouchers). Those with perfect debate attendance (Villanueva, de

There are many reasons why senatorial debates in the Philippines do not work. For one, unlike in the US where a single senatorial race is ultimately reduced to a battle between two candidates, we elect 12 senators using a multi-party system that produces too many candidates. Multiple candidates create logistical and policy nightmares for debate organizers, allows candidates to excuse themselves since they know others will show up, and reduces the time allocated for each aspirant to answer questions (http://vote2013.verafiles.org/too-many-bets-too-little-time-for-election-debates/).

Second, political coalitions do not produce coherent platforms of government. Both Team PNoy and UNA are a mixed bag of political parties bound together by a “Daang Matuwid” mantra and “responsible opposition” tag without categorical positions on most issues. We can never make debates highlight competing choices nor force candidates to explain at length the details of their programs under this scenario.

Finally, even with the limitations imposed by sound bites that rarely educate the public, most television stations have improved their debates by tapping experts from the academe and industry to test the policy positions of candidates. But they have been unable to force or shame candidate who

So how do we make debates in the Philippines count? We can

- Create an independent non-partisan Campaign Commission that will organize the debates and require candidates to participate. The debates should be done on free television and cost-shared by major networks, COMELEC, and the academe.

- Bring the debates to the regions to ensure that regional issues are discussed and regional stakeholders can hold side sessions for candidates with their respective constituencies.

- Expand the reach of social media and do serious voters education in between elections targeting poorer households and communities

. Finally , work towards reforming the political party system to make sure we have candidates who truly represent constituencies, support significant issues and have substantial platforms.

Prof. J. Prospero E. De Vera III, DPA is the University of the Philippines System Vice President for Public Affairs. Dr. De Vera teaches Public Administration at the UP National College of Public Administration and Governance in UP Diliman. He has spent the past three decades in the policy arena working in the legislative and executive branches of government in the Philippines and the United States.